Lessons from Pirates? Not Quite.

Wired (and WELL) co-founder (and all around writer/blogger/lecturer/savant) Kevin Kelly has written an interesting blog “How to Thrive Among Pirates” wherein he extrapolates lessons Western film producers could learn from the piracy-ridden filmmaking cultures of China, Nigeria, and India.

Wired (and WELL) co-founder (and all around writer/blogger/lecturer/savant) Kevin Kelly has written an interesting blog “How to Thrive Among Pirates” wherein he extrapolates lessons Western film producers could learn from the piracy-ridden filmmaking cultures of China, Nigeria, and India.

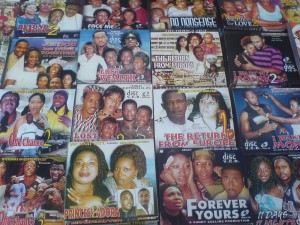

The short summary, for those unfamiliar with China/Nollywood/Bollywood filmmaking, is that there is a thriving low (or no) budget domestic filmmaking culture in these countries which one would presume would be impossible, given the widespread piracy in each.

It’s a very comprehensive, well written read – but I think his conclusions miss the mark, and often gloss over (or conveniently ignore) some of the realities of the situations and solutions he raises.

What do these gray zones have to teach us? I think the emerging pattern is clear. If you are a producer of films in the future you will:

1) Price your copies near the cost of pirated copies. Maybe 99 cents, like iTunes. Even decent pirated copies are not free; there is some cost to maintain integrity, authenticity, or accessibility to the work.

The problem with this approach is that Kevin is thinking in terms of the lessons he’s learned in three countries where physical media is the primary distribution channel of pirated material. In the west, the “cost of a pirated copy” for many movies is zero (or, at best, the pro-rated cost of a low-end computer and a couple of hours of internet time to snag a torrent. This, in most cases, doesn’t even get you a fuzzy multiple-generation bootleg, or shaky handicam movie, but a pristine, DVD-quality film – better than what you’d get at most theatres in Nigeria or India.

Let’s assume we ignore this tricky reality for a moment – there’s still a fundamental problem with Kelly’s assumption about film pricing when you apply digital rates to physical mediums. I recently talked to a number of Canadian duplication houses on quotes for replication and packaging of a very vanilla DVD for a run of more than ten thousand units. The quotes I got back averaged around $0.83 per unit for a bare-bones disc and clamshell that would meet the bare minimum of retail requirements (which are – be robust enough to survive packing and shipping to retail). Let’s assume I could, with some more volume, manage to get that per unit cost down to $0.75. So that leaves us with 24 cents on a 99-cent purchase. Now retail has to get their cut – the most I could offer would be 50% of that remaining 24 cents… but why would anyone stock that product? Compare the operational costs of a pirate DVD market stall in Nigeria and a Best Buy in Winnipeg. One has significant rent, wages, insurance to pay… even Amazon, with their tremendous volume would have a hard time justifying stocking a product with a profit margin to them of 0.12 cents per unit (someone’s got to box and ship that sucker). Of the remaining 0.12 the producer would still have to cut at least one (and usually two or more) distributors of some stripe in… let’s be charitable and say they’d only take 6 cents… if all these miraculous stars aligned (and lets be frank, I’m trying to prove a point here, no retail, distributor, or wholesaler would touch this hypothetical release) the producer would pocket – at most – 0.06 a disc. Which would mean that if you sold 33 million copies – one DVD to every single man woman and child living in Canada and the United States – you could perhaps break even on a budget of $10 million dollars (presuming you have very conservative P&A costs). Incidentally, the average cost of a Canadian feature film, is ~$3 Million, and an American film is ~$20 Million. Do the math.

Of course the (rational) response then would be “make films cheaper” – which is true… to a point, but there’s a huge elephant in the room relating to the disparity in production cost between producing a domestic film in China / Nigeria / India and the Western countries. An average Nollywood film costs between $10,000-20,000 (Wikipedia would suggest a touch higher but I’m basing on figures from a “Nollywood” panel I moderated at TIFF last year which included Nigerian super-producer Peace Aniyam-Fiberesima). Thats a factor of hundreds less than an average Canadian film, which is itself a factor of ten less than an average US one. But this isn’t because of massive profit taking, or pork, it’s a higher overall cost of living and that Western filmmaking nations cannot grossly exploit a large, extremely poor, labour pool.

No matter how cheap I propose a budget (even working guerrilla style), if it’s a commercial project I still will encumber minimum, unalterable, costs such as minimum wage, workers compensation, general liability insurance, and the maximum number of hours you can work a crew in a row before the police show up. That’s presuming I can avoid ever having to deal with a union, or an artist who would like to be paid something resembling a living wage. Even shows I’ve done entirely with donated cast and crew have cost more than a Nollywood budget on pizza, gas, and beer. And I’ll let you in on a dirty little secret that film schools don’t want you to know: Even the most amazing low-budget success stories from the independent film movement (“Paranormal Activity”, “Clerks”, “The Blair Witch Project”, “El Mariachi”, “The Celebration”) still required hundreds of thousands (in some cases millions) of dollars of post-production work (and tens of millions of dollars in P&A) to get them to the finished product audiences saw in theatres and video rental stores. The “average” Nollywood / Bollywood film would be unwatchable to Western audiences (I’ve tried, and failed, to watch several, and I’ve got a really high tolerence for production value).

2) Milk the uncopyable experience of a theater for all that it is worth, using the ubiquitous cheap copies as advertising. In the west, where air-conditioning is not enough to bring people to the theater, Hollywood will turn to convincing 3D projection, state-of-the-art sound, and other immersive sensations as the reward for paying. Theaters become hi-tech showcases always trying to stay one step ahead of ambitious homeowners in offering ultimate viewing experiences, and in turn manufacturing films to be primarily viewed this way.

Again, I don’t argue with the logic of Kevin’s point here – just that he’s glossing over an uncomfortable truth… that – increasingly – the theatre experience is *worse* for Western audiences than the home viewing ones. While the Indian and Nigerian theatres in Kevin’s article offered better fidelity and air-conditioning, my local Cineplex offer a lovely technical experience (most of the time, I have had more than once had to report an out-of-focus projector or mis-set aspect ratio or sound setting), but relatively expensive tickets, extremely expensive food, and a theatre full of people talking and using their cell phones. Ironically this is a positive feedback loop – the better the average home-theatre experience gets, the worse the average audience they behaves in public theatres because they’re used to watching films at home where such behavior is common. 3D (like THX and Dolby Digital in the 90s) will briefly keep the fidelity gap from closing entirely, at least until home televisions catch up (and 3D TV is a only couple years out at most for some reasonable early market penetration)… but where do you go from that? Certainly I still prefer the shared experience of seeing some types of films with large groupsm but I have several friends, film fanatics in their 20s and 30s, who refuse to go to the theatre any longer. Period. As home electronic and computer equipment get cheaper and higher quality theatrical is going to increasingly become just another marginalized niche exhibition platform.

3) Films, even fine-art films, will migrate to channels were these films are viewed with advertisements and commercials. Like the infinite channels promised for cable TV, the internet is already delivering ad-supported free copies of films.

I don’t really have an argument with this point per se, rather just the comment that as more film material is constantly available on multiple platforms (what I referred to in this post as the “pervasive library”) the value of each individual piece in that library decreases. Hence ad revenue on television and new media platforms will decrease with the increase of material available on those channels. That’s not to say that producers shouldn’t try to squeeze every cent out of these revenue streams (we’re trying, trust me) but also that as on-line platforms offer new sources of ad revenue, the value to be had from traditional television licenses is decreasing significantly – so it’s not a positive-sum game (and sadly the reality is that it’s not break-even either… broadcast license revenue is significantly less than what it was even a few years ago – and no on-line platform that exists yet comes close to making up the difference). There are other problems with relying exclusively on ad-supported revenue (especially with financing projects) – but that’s a post for a different day.

The other huge issue with using those particular countries as case studies (which Kevin readily acknowledges – but avoids come conclusion time) is that they are heavily subsidized by organized crime – as laundering opportunities, and vanity projects – so how sustainable they’d be entirely on their own merits is debatable. That’s not to cast aspersions on any film creators working in Bollywood/Nollywood/China – but even their staunchest artistic supporters would have to admit that a large portion of their industrial infrastructure (from venture capital, through the star system, to distribution) is tied up heavily with organized crime, money laundering, and the black/grey markets.

Having said all of that, I certainly think there are certainly valuable lessons to be learned from all of these national cinemas. I’m just not sure Kevin concludes with the right ones. Fundamentally I don’t beleive these systems are sustainable without a large, mostly poor, audience, highly exploitable labour, and cash influx from organized crime.

Incidentally one conclusion where Kelly and I are right in agreement is that legitimate distribution methods have to be as convenient (if not moreso) as illegitimate ones. I find it quaint when the National Post crows that retail piracy is down because of police raids. Retail piracy is down, because it’s a pain in the ass compared to booting up your favourite torrent engine, and having a film in twenty minutes. Zero cost, remember?

Another point I do always take from these film cultures is their liveliness, a willingness to buck traditional production values, assumptions, and techniques and a real “can-do spirit” that’s infectious. My favourite part of “Peace Mission”, Dorothee Wenner’s solid documentary on Nollywood, is an interview with a young man running his own CGI company in a small town. His work certainly isn’t going to be mistaken for WETA anytime soon – but every time I’m shocked when, after a clip of a giant robot shooting up Abuja, the young man proudly shows off his “workstation” – an original pentium 90 with a cracked copy of 3D Studio Pro. That attitude has been at the heart of film since the Lumiere’s, and the moment the industry ignores it, is the moment that “the industry” is no more.

(edit 04/09/10 – Moved some paragraphs around to better consolidate a couple of points)